I just finished my poetry book.

Long before Rupi Kaur and other Instapoets went viral for their iconic feminist poetry, I wrote my first book at 18, followed by my second at 21. They were called Bridge to My Soul and Garden of My Soul. However, as a perfectionist, I thought they weren’t good enough, so I decided to take them down before they could gain traction.

My love for poetry goes way back.

I fondly remember reading a vibrantly illustrated copy of Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses, which was a significant part of my childhood. I was that nerdy quiet girl who would read The Children’s Classic Poetry at recess. I probably had more poetry books on my shelf than anyone else in my class. And I was also Emily Dickinson’s biggest fan.

In 5th grade, people would make fun of me for being so heavily invested in checking out the maximum number of books I could borrow from the library and they’d all be Emily Dickinson books. I even recited an Emily Dickinson poem in front of the class and received extra credit for it. It was called “Will There Really Be a Morning?”

But I was hurt when I heard a kid say, “I hate poetry because it’s a waste of time.” And everyone else in the class seemed to agree. I guess because it was cool to diss on poetry. And that thought bothered me for a long time.

When I was 12, I expressed a fervent interest in writing poetry for a living, but people would scoff at me and say, “Go get a real job,” or “Study something useful.”

It felt like poetry simply had no place in a culture that valued image-based success and profit over individuality and honest self-expression.

In despair, I’d sulk and shut myself off from the world and I’d begin furiously writing poetry. No matter how busy I was with school or how much I was struggling with depression, which adults mistakenly labeled as “teenage angst,” I kept writing.

Not all of it would make sense, but it was cathartic and definitely more productive than partying or dating. I felt like an imaginative child and a wise old woman who were coexisting in one body, as normal adolescence was completely alien to me.

Then poets like Lang Leav and Rupi Kaur went viral and poetry as we know it had become more profitable for publishers and more engaging to Millennials, which my younger self couldn’t have foreseen.

During my early 20’s, shortly after quitting engineering and rushing through a math program at the last minute by overloading my schedule, I couldn’t cope with hundreds of job rejections and the incessant pressure to prove my worth with, albeit, superficial forms of success.

I was feeling like a failure, and I couldn’t cope with the fact that my peers (who previously weren’t poetry people) gushed over how Rupi Kaur’s book was so amazing, while they casually made offhand comments about how dumb and naïve I was to even consider poetry as a career. Rubbing more salt into my open wounds. During these darkest times, I was resentful of anyone who was condescending towards me for failing at something very difficult, which they themselves didn’t have to face. The label “tortured artist” suited me then and it suited me well.

And the burning question that catalyzed my resolve to finish a poetry book was this: “Why do people worship and look up to those who seem to have attained astronomical success so quickly in a creative field (or a dream job), yet they look down upon those who have the same interests and aspirations?”

I’ve been told far too many times to count that all I had in my hands was a fragile pipe dream. I’ve been told that I was just a shabby nerd who wasn’t marketable enough.

That I wasn’t outspoken, fierce, or controversial enough like Rupi Kaur to make it big as a poet. I was always the quiet girl and quiet girls finish last.

I wanted so badly to finish my third poetry book by the time I turned 23. But that didn’t happen. It was possibly the most difficult year of my life, especially when I saw everyone thriving on social media, traveling to exotic destinations, creating things that seemed to go crazy viral every time they put something out there, and becoming managers at 22.

My creativity seemed to have left me and I had frequent mental breakdowns due to immense guilt, which repeatedly kept telling me “You are lazy, talentless, spoiled, and unworthy.” It became my mantra, and being the triggered pessimist I was, I believed that I couldn’t make it and should just give up.

And I did for a time.

But later I experienced a slow but steady breakthrough.

I didn’t begin writing poetry again until last summer. It all started with just one new poem a day. I didn’t pressure myself to produce a book like a machine because I’ve found that the more I pressured myself, the more I froze and blocked my own creativity.

During work breaks, I’d walk over to the Barnes and Noble across the street, order a black coffee, and scribble down lines and ideas that I’d wanted to come back to later and turn into a poem. And many late evenings after work, I’d just sit in the back of my car and write, just to prolong the time I had completely alone. I was suffering and lost, but it felt like no one cared. Well, I could tolerate indifference, but having my dreams mocked was another level of pain that I couldn’t handle well.

By the time I gathered just enough poems early in 2019, I found the motivation to write a book again. I wanted to have the first draft done by April, so then I’d stay up way too late to churn out as many as 50 poems a night, so feverishly and obsessively.

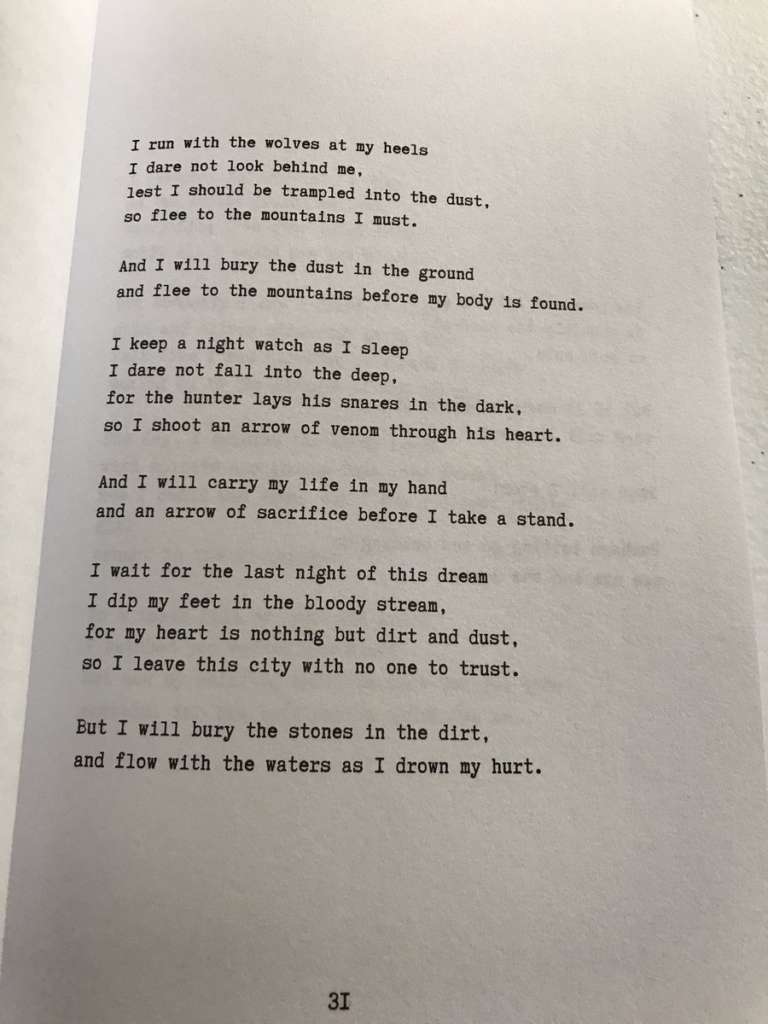

I would write about all the pain, the guilt, the loneliness, the silent yet forceful terror in my chest, and the way I yearned for connection in a world starved of it, a world that profits off of dreamy, unattainable standards while cleverly marketing it as “authenticity.”

When poets wrote things I couldn’t personally relate to, I still admired their own unique voices and appreciated their dedication to their craft. However, I’ve always felt that there was something missing in the poetry world, which was deep introspection and as an Enneagram 4, I craved more modern poetry books like that.

And as much as I love seeing other poets empower themselves and defy societal norms, I’m an introspective person who likes to see variety in art, and poems that mainly talked about interpersonal relationships weren’t relatable.

Instead, I wanted to read more poems about spirituality and soulful matters that transcend the strife of today’s world.

I wanted to read more poems about not fitting in during my 20’s and being misunderstood.

I wanted to read more poems with allusions to classic folk songs.

I wanted to read more poems that made good use of abstract symbolism and techniques from the greats but seamlessly combined that with today’s writing style.

I wanted to read more raw and personal poems about what it truly means to feel unwanted. To be a failure, an outcast, and a loser who struggles with navigating through life without direction, to be unknown and lost in the void.

A few months later, I finally wrote the book I couldn’t find anywhere else. The book I’ve been seeking for my entire life.

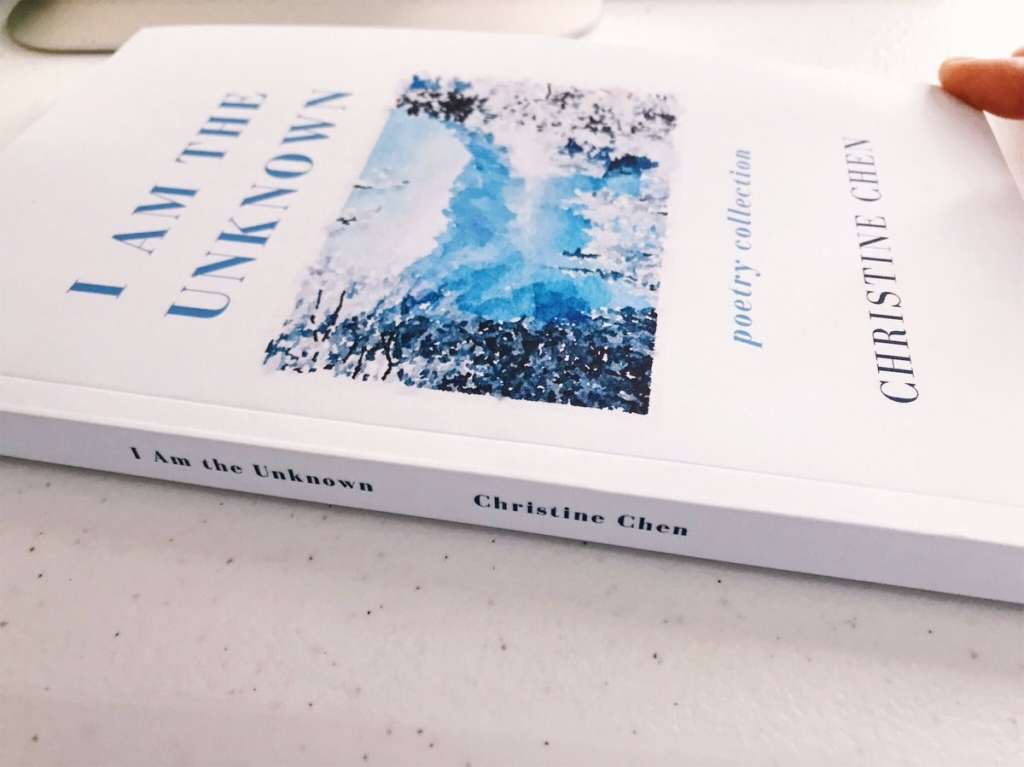

I came up with the title I Am the Unknown because the central theme that ties these poems together is the idea of being obscure, left out, and losing your sense of identity.

I was well aware of how arduous the road ahead would be as a poet, but I had to do it, and alone too. I had to level up and fight tooth and nail for myself because simply writing wasn’t enough.

I had to prove that I can complete a large project without any expectation of reward in the end. If I had to lose sleep, never have a social life, never buy anything I want, and never gain the approval of anyone, I was still willing to do it because in the end, my own self was all I had and I couldn’t rely on anything else.

Sometimes, I felt the fires scorching within every fiber of my spirit as I wrote poems about my struggles, while other times, in contrast, I felt completely at peace as I wrote about little miracles that brought me joy and hope, the ones I’ve often taken for granted.

But in the end, I realized it was never about me.

It was never about proving myself worthy with my talents to get back at all those who have doubted me and called me a perpetual failure. It was never about the popularity or jumping onto the contemporary poetry bandwagon at its most profitable state. Those distractions and external rewards were frivolous because my aching soul longed for another form of healing that I could only create for myself, the kind that must originate from within.

The journey was all about sharing my truths, expressing myself in a way can’t be replicated by anyone else, and proving to myself that I am lovable, strong, and worthy as I am, regardless of some arbitrary scale of value that definitely had me at the bottom of the barrel. Regardless of how others perceived my level of competence and value based on their standards.

While I originally wrote it to cope with my overwhelming sense of shame, my depression, my disconnection from society, and my existential crisis, I could also feel the pain of people around me as well, even when they constantly pretended that everything was fine. Keeping that in mind, I honed in on what my purpose was for the book. I knew it had to be more than just a collection of poems for myself and it must come from the most honest and vulnerable place in my heart.

I wanted it to be a constant friend to those who feel lost and unwanted.

I wanted to share pieces of my soul so that maybe someone else out there may find a kindred spirit in me and see how wondrous life can be even after the most furious of storms that we keep raging against.

I wanted to let people know that you can choose joy. The weight of despair doesn’t have to prevent you from it.

I’ve come to realize that after finishing my book, I’m worrying less about popularity than I used to. Milk and Honey is a great book that brings me hope as a poet — it shows that poetry has more of an impact on this generation than I previously thought. I’ve accepted that fact that my book is very different from Milk and Honey and it probably won’t ever be picked up by a big publishing house since I’m the quiet girl who leans more towards softer and more melancholy forms of expression. But I have my own writing voice and my own set of experiences, which may not be as popular and that’s okay for me since the greatest reward I’ve gained was solidifying my identity and being more connected with inspiring female poets in the contemporary poetry community.

After years of postponing this project and pushing it by the wayside when life got in the way, I finally feel like I’m a doer and not just a dreamer.

I finally feel like I’ve found my voice again, which is still quiet but has grown more resonant and bolder. And that’s immensely reassuring and worth all the sleepless nights.

Even though I have no idea what the future holds after releasing this book, I know that it was the most rewarding endeavor I’ve ever done thus far. It was my personal testimony of how I conquered the worst within me and emerged as a victor, not perfect by any means or even measuring up to someone else’s unrealistic standards, but as myself — openly, honestly, and truly me.

And I hope that this message resonates with readers who are struggling with being unknown and venturing out into the unknown.

And I hope that they find freedom in embracing the unknown out there and within themselves.